In the spring of 1925, thirty educators gathered in a classroom at Nashville's Hume-Fogg High School with a clear diagnosis: interscholastic athletics was untethered from educational purpose and change was necessary. "Student-athletes" often weren't legitimate students, eligibility standards varied wildly between schools, and officiating lacked consistency. These principals and superintendents believed athletics could enhance education as part of the overall school program—but only if educators themselves controlled the boundaries.

A small but dedicated group of these school leaders established the TSSAA with a straightforward mission: ensure athletics served the school, not the reverse. This principle would guide Tennessee school athletics for the next hundred years, withstanding countless pressures from those who would use athletics as a vehicle for self-aggrandizement rather than as an educational tool maintained for the good of all.

The First Meeting

The initial meeting was led by G. C. Carney, the principal of Nashville Central High School, and A. J. Smith, the superintendent of the Clarksville School System. Drafting a basic agreement amongst themselves, they gave their work a name—Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Association.

By the time they adjourned, Carney was president, Smith secretary-treasurer, and the first Board of Control had been elected, with vice presidents from each Grand Division—James Lovell (Bradley Central High School), Frank A. Faulkinberry (Franklin County High School), and B. L. Hassell (Peabody High School, Trenton) with two additional members appointed in Stacy E. Nelson (Chattanooga Central High School) and W. A. Bass (state high school supervisor).

They borrowed no authority except the moral kind that comes from running schools every day.

Twenty-four schools filed applications at once; forty-five were members by the end of the first year. The dues were five dollars. The idea was larger than the fee.

The Association’s declared purpose was “to stimulate and regulate the athletic relations of the secondary schools of Tennessee,” public and private. The word “relations” carried great weight and meaning: games were often hotly contested, but schools, as institutions, had to live together after every buzzer, and they needed predictable ways to do it.

The architecture of the new Association followed those Grand Divisions. By 1930, the Board of Control had expanded to a full nine-members, three from each Division, and was the executive arm and final court of appeals for the organization. By rule, they were principals or superintendents, and the three from each Division functioned as a Divisional Committee, empowered to organize locally and rule on matters in their region, subject to appeal to the full Board. The officers—a President and a Secretary-Treasurer—were elected by the Board, and the Association would hold its annual meeting during the State Teachers’ Association Conference in Nashville. A quorum was twenty member schools and five Board members.

Rulemaking Matures

In these early years, changes to the Constitution and Bylaws were made by direct votes of the principals. Changes required a two-thirds majority. It was messy—the hallmark of a pure democracy–and became unwieldy as the membership grew.

The first procedure was to vote during the annual meeting, but the membership soon realized that the growing size of the group and the lack of preparation and prior contemplation contributed to hasty rule changes which were oftentimes unwise and soon reversed.

Before long, the Association moved to changes by referendum. By 1934, however, TSSAA's Secretary F. S. Elliott reported that the referendum-by-mail program was an expensive undertaking and that the rate of response was declining with each passing year.

The Association took a step forward at the annual meeting in 1935. Borrowing a model other states had found effective, the membership created a Legislative Council, with one member per Congressional District (nine at the time), to specialize in lawmaking. The Board of Control retained its judicial and executive roles—enforcement, appeals, expenditures, registration of officials—while the Council handled the Constitution and Bylaws. The two bodies were firewalled: no one could serve on both. Proposals would flow up from schools through three regional meetings (East, Middle, West) each fall; the Council would gauge sentiment and vote in its annual spring meeting.

Less a Foundation, More a Reason for Existence

The Association is a pact to avoid a “prisoner’s dilemma.” Everyone has an incentive to cheat. Winning is everyone’s goal. But if everyone cheats, and the cheating inevitably escalates, the result is the destruction of what makes school sports worth having in the first place.

The 1930 handbook—printed, stapled, and mailed to every member school—contained only five basic eligibility rules, but they stand at the heart of the purpose of TSSAA.

Scholarship: A student had to pass three full-unit subjects the previous term and be passing three in the current term. A “pass” was 75 percent, and summer-school makeup work did not count.

Term Limit: Ten terms of attendance (or fifteen three-month terms) was the lifetime maximum. One play in one varsity game burned an entire season.

Age Limit: No student could compete after his twenty-first birthday.

Transfer (Migratory) Rule: A student who changed schools without a corresponding change in his parents’ residence sat out twelve months in that sport.

Amateurism & Rewards: No pay for play, no gifts worth more than one dollar, and no officiating for money. Medals, cups, and school letters were allowed; everything else was suspect.

Each rule is a credible commitment by individual schools to restrain short-term advantages so that together the schools may preserve educational competition over the long-term.

Students must actually be students. Players must be of school age and therefore get a limited time to play. And you play for the team where you go to school.

If talent can be legally aggregated wherever it wishes on short notice, you no longer have school teams but regional all-star clubs in school uniforms. If sport becomes a cash market, the educational frame is displaced by recruitment, sponsorship, and bidding.

You can renovate the kitchen or add a deck, but mess with the foundation of a house and the whole thing may easily collapse.

Responsive Rule Making

Some rules have come and gone over the years, in response to changing circumstances. Of note during the period between 1925 and 1942:

Playing on Teams in Higher Institutions: Adopted in 1931, the rule stated that no person was eligible who had ever attended college or played on a normal school, junior college, college, or university team. An exception for students whose scholarship only allowed entry into classes not beyond the senior year of preparatory schools was initially made, but removed in 1936.

Student Dropped from School: A student who dropped out before the end of a term was ineligible until they had been back in school a full term and passed in three subjects.

Student Service: From 1931, a student holding a position such as librarian, monitor, secretary, janitor, or waiter (or any other position for which they received financial consideration) was ineligible unless the Divisional Committee decided the service rendered was adequate return for the concession.

Tuition: If tuition was charged, it was presumed to be paid by someone concerned with the student's welfare. The 1931 rule stated that scholarships granted by school authorities should be based on adequate grounds, and outside payments for athletic interest were viewed with suspicion. Divisional Committees could request information for eligibility protests. Ministerial students and sons of ministers receiving free tuition were exempt. In 1936 the rule narrowed to require tuition be paid by a parent or bona fide guardian, and scholarships could not be granted for athletic purposes (their basis had to be approved by the Divisional Board).

Teams Which Member Schools May Play: Initially, TSSAA schools were permitted to play alumni and freshman college and junior college teams. After January 1, 1931, playing non-TSSAA schools in Tennessee or schools outside Tennessee not part of their state's athletic association was prohibited. In 1935, the rule was relaxed to also allow contests with members of the Southern Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools. The Southern Association clause was scheduled for elimination in 1941 but was reinstated in 1942. An exception for one alumni game and games against college freshmen persisted through the period.

Other rules we have come to know today were added during this period.

Time of Enrollment (or Enrollment Rule): A student had to be duly enrolled by the twentieth day after the beginning of the term to participate in sports that term.

Recruiting Rule: Introduced in 1936, the rule stipulated that the use of "undue influence" to cause a student to transfer for athletic purposes would render the student ineligible for twelve months and penalize the school.

Eligibility Lists: Initially, team managers were required to mail a principal-certified statement of eligibility to the opposing team five days before each contest. Principals had to furnish eligibility information upon request or risk being removed from membership. Beginning in 1936, eligibility lists for each sport, containing the names of all participating students, had to be filed with the Divisional Secretary and State Secretary-Treasurer before the first game. Students joining the team late had to likewise be reported before a student participated, with a penalty of sixty days' suspension for violations. By 1939, failing to return participation lists, rating sheets, or other requested blanks also carried this penalty.

The two decades following 1925 were a time of dynamic evolution for TSSAA, as the membership adapted the rules to close loopholes and address new challenges. The early set of rules defined the organization's very identity.

Together, the school leaders worked to construct a defensive wall around the school day, the school year, and the principal’s authority. With rules focused on academic progress, age limits, transfers, and amateurism, the bylaws established a sound philosophical core, ensuring that athletics remained a component of education, not a professional enterprise.

Rules to Live By

The handful of principals who first drew up the TSSAA constitution understood something crucial: competition is only meaningful within agreed-upon limits. Remove the limits, and you don't get better competition - you get chaos where the strongest players write their own rules and everyone else goes home.

These weren't just rules about sports - they were rules about how to live together. Schools are neighbors. They have to schedule each other, accept referees' calls, honor results, and do it all again next season. That only works if everyone believes the game is fair and worth playing.

Break that trust, and you don't just lose a sports association - you lose the idea that institutions can cooperate for something bigger than themselves.

Against all odds, the Association they built remains what they intended: a non-profit confederation, not tax-supported, funded by the gate receipts of the postseason and the help of corporate sponsors, led by school administrators, and bounded by written rules.

Every policy answers, “How does this serve schooling?” If the answer is “it serves winning,” it is a violation of the association’s ethos. It is not anti-sport; it is radically pro-school.

Properly functioning, the Association is an impediment to those who believe a successful sports season is the secret to success in life, and not an education, honestly earned.

While today’s culture may reward glare and reaction, TSSAA’s work remains as clear and necessary as ever: process over noise. Meetings on the calendar, proposals in writing, votes tabulated, officials registered, eligibility lists filed, sanctions issued, and, as always, with the name of a principal at the bottom of the page.

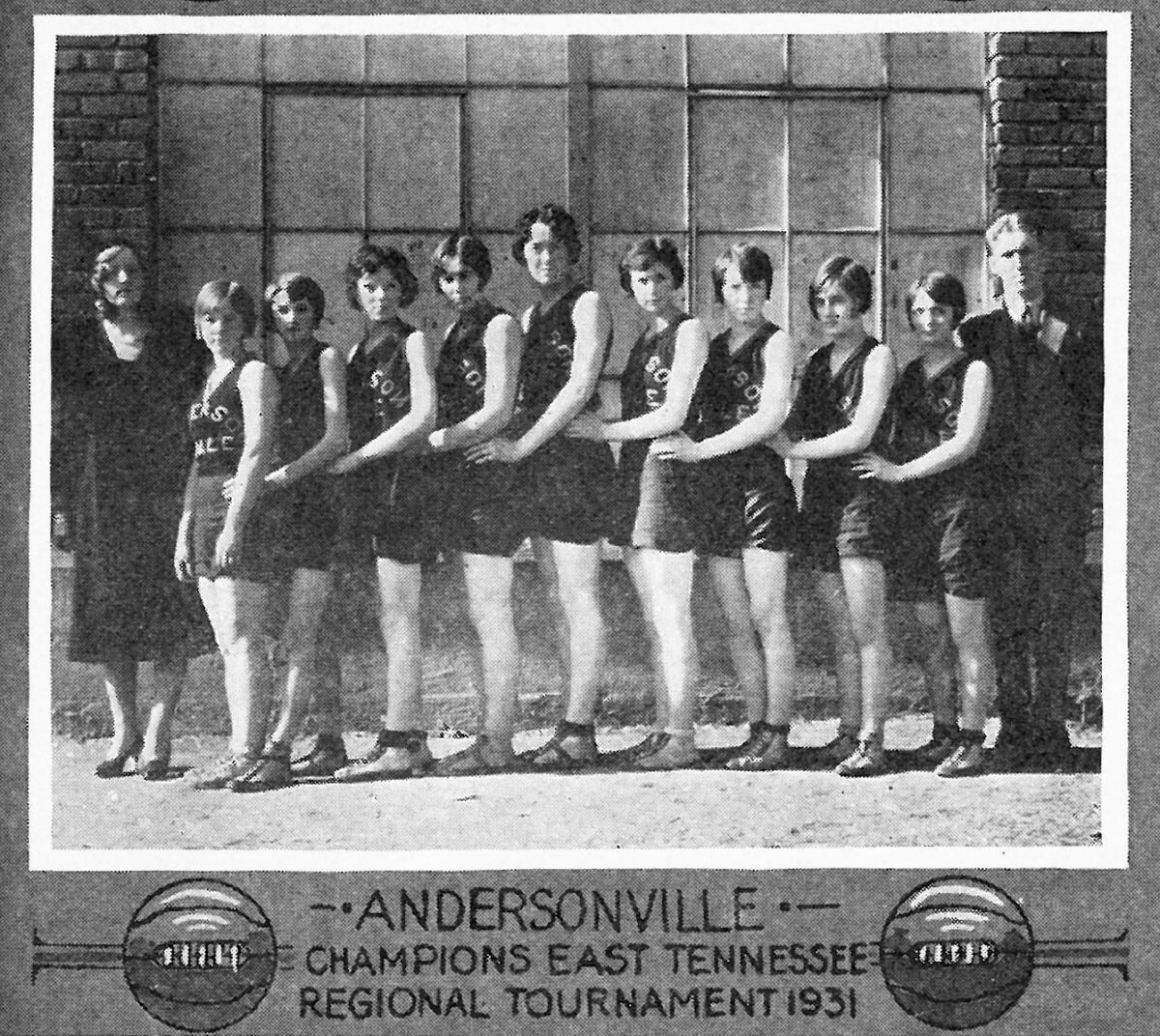

1931 East Tennessee Girls Basketball Champions - Andersonville

Early Evolution of Transfer Rules (Migratory Rules)

1930-1931: A student transferring schools was barred from competition for twelve calendar months in the sport they had participated in, unless the transfer was due to a change in parental or guardian residence or completion of studies at the former school. Specific exceptions were made for students completing certain grades or transferring from two-year to four-year high schools. Students were required to live at home with parents/guardians if they participated in athletics, and bus route changes did not affect eligibility.

1935: The rules were codified under "Transfer Rules," maintaining the twelve-month ineligibility for transfers without a corresponding change in parental residence. Exceptions were added for out-of-state transfers to private TSSAA schools. Athletes were required to live at home with parents or appointed guardians (with Divisional Board exceptions possible, and private school students supervised by faculty exempt). Students completing studies could transfer, and two-year high school students could transfer to higher-grade schools after one year.

1936: New provisions made students eligible if they transferred from schools that lost their State Department of Education rating. Also, students whose school residence changed due to bona fide bus route changes by the County Board of Education or Superintendent did not forfeit eligibility within their own county. Students ineligible in another state automatically became ineligible in Tennessee.

1937: The "within their own county" restriction for bus route changes was removed. A rule was added that students living in one county and attending school in another were ineligible unless the resident county's Board of Education contracted with the other county and paid tuition.

1938: The cross-county tuition rule from 1937 was removed. The bus route change rule continued without the "within their own county" limitation.

1939: A major change made a student, with or without an athletic record, ineligible for twelve months in all sports (previously "that sport") if they transferred without a corresponding change in parental or guardian residence on or after October 1, 1939.

1940: Further clarification stated that if a transfer was due to a change in parental/guardian residence, the student would be ineligible until the Divisional Board of Control reviewed the case and declared them eligible.

1941: The ability for the Divisional Board of Control to make exceptions for "manifest injustice" regarding athletes living at home with parents/guardians was removed.

1942: This rule removed in 1941 was re-added, allowing the Divisional Board of Control to make exceptions for "manifest injustice" regarding athletes living at home, but only "after the student has been in school twelve months from date of entry".